"Look! A Negro." Frantz Fanon, BSWM

PART 1: A Story

You bundled up in your wool coat, doubled checked the contents of your bag (microphone, iPad, iPhone, wallet, notebook, pencil case, chargers), and grabbed your travel mug. You’d read on a travel blog that you’d need to bring your own to-go mug in Spain because it was common to sit in a café rather than take your cafécito to go. You headed down the stairs and out onto the streets of La Latina, an auspicious name you thought, for the neighborhood where you were staying while doing field work for your soon-to-be-completed dissertation. You walked by two fruit shops and ducked into the café bar. You ordered a cortado and ignored the smirk on the face of the barista, a middle-aged man with dark hair and eyes. He tapped his finger angrily on the counter when you attempted to pay by putting the euros in his hand. You realized that he didn’t want to take money from your hands but that morning you’d decided he was just grouchy. You left some coins, a tip, on the counter and he pushed it back at you and dismissively snapped that he was insulted at the gesture and that he made enough money without having to take yours. You shrugged your shoulders and walked out, trying to find your way to the bookshops you were told would have the materials you needed. At the first bookstore you were ignored even though you asked for help twice. You found the Africa section near the front of the shop and you collected every copy of a book written by an Equatoguinean author. You’d come to Spain to collect as many books on history, politics, race, and literature, as well as to conduct interviews with diasporic and exiled writers from the only Spanish-speaking Sub-Saharan African nation-state. You piled the books onto the counter and to the surprise of the clerk you paid over 300 euros for your new collection.

You decided to skip the second bookstore because you had only 20 minutes before your first meeting with a retired Spanish political scientist whose area of expertise was Equatorial Guinea. You’d agreed to meet at the corner of the department store El Corte Inglés but you hadn’t secured a SIM card and without wifi your cell phone did not work. You told him you’d be wearing a burgundy coat, and that you had brown skin and curly hair. You thought that would be enough for him to spot you. You headed to the corner of El Corte Inglés and stood under the awning near the bus stop avoiding the drizzling rain. Ten minutes turned into twenty and twenty into forty. You paced a bit and kept your eye out for this señor. You’d gotten a little turned about and didn’t know where you were or how to get back to your apartment. After almost an hour you decided to ask the woman standing next to you to make a phone call on her cell phone and even offered to pay her a few euros for the trouble. You’d felt comfortable asking her because she reminded you of your mother, a short, fair-skinned, late-middle aged woman with a seemingly kind face. Little did you know that your request would be met with disdain. Perhaps it was the sound of your Puerto Rican accent, your fast-paced talking, or your Blackness. She pressed her purse tightly and replied: no. No, you could not use her phone and what were you doing in Spain anyway? You explained that you were a doctoral student doing research and that you were waiting to meet someone you were supposed to interview. She didn’t believe a word you said but she was your only hope at the moment, so you pressed on. Señora, you can hold my phone while I make a phone call on yours you offered – knowing that your smartphone was more valuable than her flip phone and perhaps that gesture would put her at ease. She acquiesced only after you made the suggestion twice and clutched your phone in her hand giving you an icy look as you triangulated your location with your contact. When you finally found each other, the old man scolded you for being on the wrong corner. You accompanied him to a café where he talked to you about the exceptionality of African dictatorship and how its violence went beyond any colonial influence. African violence, he pressed, was its own phenomenon altogether. You countered his argument to no avail and suddenly became distracted. You were being watched. You realized that the waitstaff and a few patrons were looking oddly at you and your interviewee.

One evening a few days later you’d gotten lost on the metro and with no cash in hand you had to walk back to La Latina. As you came up from the station you realized you were on a desolate street. Three men walked out of a building and you approached them asking, “¿permiso, me pueden ayudar?” Two of them brushed past you and the third one yelled, “¡NO ME HABLES!”. The fury flew out of your throat and whatever you said to them made one of the men double back and apologize to you but even then, he wouldn’t tell you what direction La Latina was. After about an hour of walking you found your way back to the apartment.

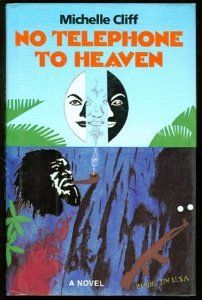

The following day you took the train to Barcelona where you were going to meet with and interview two Equatoguinean writers Juan Tomas Avila Laurel and Remei Sipi Mayo. This would be the first interviews with Equatoguinean writers in Spain and you were excited to meet with them and discuss your upcoming trip to Equatorial Guinea. When you arrived at the station Juan Tomas picked you up and took you to a bookstore and later to the home of Remei. At Remei’s apartment you were welcomed with open arms. She prepared you a meal, talked with you for hours, showed you photos of her grandchildren, and advised you to go to her hometown in Equatorial Guinea ensuring that someone would meet you there. She then asked how you were enjoying Spain. You answered her honestly and told her how you felt isolated, mistreated, and had faced much rude and racist behavior. Even the express train ride from Madrid to Barcelona wasn’t without incident: the Spanish man assigned to the seat next you refused to take it and was reassigned a new seat several rows ahead. Remei listened with a knowing grimace on her face and replied: “Niña, es que creen que eres una prostituta.” She explained that in Spain Black women, especially from the Caribbean were assumed to be prostitutes. Sex workers. Whores. You sat at the table of this beloved African woman writer, surrounded by her books, with your mouth agape. Remei had opened your eyes.

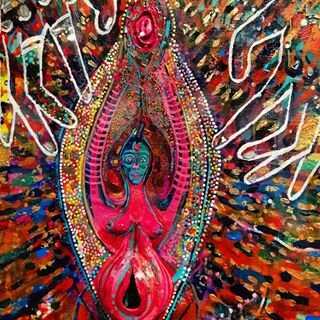

[found image/artist unknown]

PART 2: LA MIRADA

In her 2002 book, Inmigración y género, Remei Sipi Mayo examines the racialized experiences of African women in Spain. She outlines the distinct experiences that propel women from various locations across Africa to Spain. Furthermore, she enumerates the kinds of racialization and quotidian violence experienced by Black women in the diaspora. She names this violence “La Mirada,” or the reductive “gaze” through which Black immigrant women are often seen

Es aquella que surge del exterior o sea de la sociedad receptora, de aquellas

miradas que ante mujeres procedentes de escenarios humanos diferentes tienden

o pretenden encasillarnos, reduciendonos a estereotipos y aplicándonos prejuicios

como, por ejemplo, los referidos a considerar que por ser de un determinado

origen, somos prostitutas, trabajadoras del servicio doméstico y un largo, en

ocasiones, etc. Intentando borrar saberes y riquezas que algunas trajimos y los que

aprendimos aquí como maestras, escritoras, dinamizadoras de grupos, mediadoras

interculturales, etc. (22)

The violence of La Mirada reduces African and Afro-Caribbean women to the roles of sex workers or domestic workers, while simultaneously erasing the rich knowledges and skills they bring from their homelands and eliding the skills and education they acquire in exile or diaspora.

In his 1952 text Black Skin, White Masks Frantz Fanon examines the ontological and phenomenological (“ontogeny” and “sociogeny”) impacts of anti-Blackness and racialization on Black subjects. Relegated to the “zone of nonbeing” the Black (man) is condemned to continually face the bad faith of anti-Black racism and the “veritable hell” of continued dehumanization (xii). In his chapter “The Lived Experience of The Black Man,” Fanon recounts a quotidian moment of violence, the “passing sting” of a young white boy in France crying to his mother, “Look! A Negro” and “I’m scared” (90). This chance encounter, among others, forced Fanon to see himself “in triple,” to understand the lived experience of the Black man as embodied, and to see the sociocultural schema of white supremacy yield to an embodied racialized schema(92).

Fanon has long-been critiqued for his parsimonious discussion of gender and sex in general, and his terse discourse on Black women in particular. Yet, in the days after the revelation that during my doctoral fieldwork I was perceived as a whore, I kept thinking about that oft-cited chapter of Black Skin, White Masks. In my imagination the little French boy of Fanon’s story grew into the Spaniards (both men and women) who looked at me like a sexual object with no value. Within this colonial white supremacist heteropatriarchal system Black women are reduced to their racialized sex and potential to perform illicit sex acts. The fact of Blackness, for Black women, is to become the container for sexual labor, to labor for the white imagination. Gendered racialization is a production of a series of limiting categories, spaces, placements in the world. Thus, thinking about the “space between the legs,” as articulated by M. NourbeSe Philip, is a critical site to think about how Black women speak within, between, and beyond histories of oppression and contemporary forms of quotidian violence. [1]

A Black Latina perspective adds to these African and Caribbean meditations on the permanence of gendered anti-Black racial structures and attitudes. To be clear, sex work is work, perceived promiscuity is a social construct with all-too-real impacts, and the word “whore” is both fatuous and laden with meaning. In this case, the attitudes and actions I experienced in the field revealed to me how Black women assumed to be prostitutes are conceived as: suspicious, interesadas, needy, desperate, cunning. It is also imperative that we link this tacit understanding of Black women’s bodies/being as part of transnational networks of the sex trade that thrive in the Caribbean through economies of sex tourism and matrices of exploitation. [2] The space afforded to Black Latinas by La Mirada in a world mired by ongoing colonization and coloniality, is wretched.

Found Image/Artist Unknown

PART 3: BLACK IN THE FIELD

I have been thinking about the surveillance of Black people both in public and institutional spaces, and the confluence of both.[3] In January 2014 I was conducting a final round of interviews and material collections for my dissertation which focused on Blackness and the literary, aesthetic, and political relationship between the Spanish-speaking Caribbean (Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic) and Spanish-speaking Sub-Saharan Africa (Equatorial Guinea). After a week of awful experiences in Madrid, some of which I outlined in Part 1 of this post, I traveled to Barcelona to the home of writer and editor Remei Sipi Mayo. That afternoon Remei listened to my stories, commiserated with my pain, and affirmed my experiences. Unlike the many other (white Spanish and mestizo Latinx) scholars with whom I’d come to share these experiences, Remei didn’t brush the story away or reduce the blatant gendered racism I’d faced as simply “rudeness” or “Spaniards being in a rush”. Instead, Remei was one of the few faithful witnesses to my experiences and she stood alongside me helping me to reckon and recover from the deep impact of those violent interactions.[4]

Each year I tell this story to my graduate students during our “Responsible Conduct of Research" discussions. I share my experience as a Black Latina in the field for two reasons: first, to expand their understanding of field work and transdisciplinary research in the humanities, and second, to foreground the ontological experiences of Black women researchers as a way to underscore how gender, race, and gendered anti-Blackness impact the experience of scholars in the academy in general and in the field in particular.

Graduate and government institutions offer scholars in humanities and the humanistic social sciences training on archival and field work including various forms of data collection and primers on ethical human subject study. These trainings, however, are crafted in universalist terms and often assume that the scholar in the field, in the archive, and in the world, is a white man. As such we are trained to approach field and archival research as if these spaces/places would welcome us, nurture us, and accept us as they would if we were white male scholars. To be clear I was not totally naïve in my scholarly endeavors. As an Afro-Boricua -a colonial subject- going to Spain for research I was aware that I might face racism. Yet, I was also endowed with a false sense of security offered to me by my training in Comparative Ethnic Studies and by the financial resources given to me by the top public institution in the US. That is to say, I was expecting racism in general yes, but not the kinds of gendered racism and xenophobia that made quotidian encounters unsafe.

The latest uprisings in the wake of extralegal and police violence against Black people in the US has ushered in a bevy of public letters by Universities and Colleges across the US promising “accountability” and increased “diversity” efforts. If research institutions are indeed committed to recruiting, retaining, and otherwise supporting students who are radically racialized and gendered, students who are underrepresented, and students who are first-generation, then they must reject the normative underpinnings of their research agendas, trainings, and methodologies. This will not be addressed by “diversity, equity, and inclusion” training but rather by rethinking the colonial categories of research, the human, and the intimate impacts of anti-Blackness inside and outside the ivory tower. As the Combahee River Collective argued in their 1977 statement, “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” Thus, as we continue the important work of abolishing the current systems of unfreedom endemic to capitalism and coloniality, we must continue to make critical changes to our conceptions of knowledge production. One such way to do this is to take the experiences of Black women and racialized and gendered subjects as the point of departure for a profound reimagining of the practices of all scholarship.

Notes:

[1] M. NourbeSe Philip A Genealogy of Resistance: and other essays. Mercury Press (1997). See also, Katherine McKittrick, "'Who do you talk to, when a body's in trouble?: M. Nourbese Philip's (Un) Silencing of Black Bodies in the Diaspora" (2000).

[2] For more on Caribbean sex tourism, sex trafficking, and sexiles see: M. Jacqui Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred (2005); Yolanda Martinez-San Miguel, “Female Sexiles? Toward an Archeology of Displacement of Sexual Minorities in the Caribbean” (2011); Angelique V. Nixon, Resisting Paradise: Tourism Diaspora, and Sexuality in Caribbean Culture, (2015); Lorgia García Peña, Borders of Dominicanidad: Race Nation, and Archives of Contradiction (2016) in particular the chapter titled “On Bandits and Wenches”;

[3] For more on surveillance and the state see Simone Browne Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (2015). For more on the experience of “archiving while Black” see John Hope Franklin, “The Dilemma of the American Negro Scholar” (1963) and Ashley Farmer, “Archiving While Black” (2018).

[4] For more on faithful witnessing see, Yomaira C. Figueroa-Vasquez, “Faithful Witnessing as Practice: Decolonial Readings of Shadows of Your Black Memory and The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” (2015), Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature (2020); Maria Lugones, Peregrinajes/Pilgrimages: Theorizing Coalitions Against Multiple Oppressions, (2003)

[this post was first published on 1 July 2020 on the Black Latinas Know Collective site]

![[found image/artist unknown]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/557d104fe4b020deb8e1339c/1594005564358-AXASOKFBIB5EBPEB1XAX/bin.jpg)