BEGINNING

We lost our first baby in 2013. I woke up one August morning with sharp pains coming in quick succession. Bleeding profusely and confused, I fell off the bed and crawled quietly down the hall to the bathroom. I didn’t know what was happening and not wanting to wake up my husband, I kept my moans to a low treble. After what seemed like an eternity in the bathroom, I limped slowly to the couch and cried as the pains swelled across my body over and over again. I remember thinking: if this is what childbirth is like I don’t want it.

Later that morning we tried to figure out what was happening: food poisoning? a bad period? a cyst? a physiological reaction to the blow out fight I’d had with my brother the afternoon before? After a few hours I was able to withstand the cramping and decided to keep my plans to visit a friend who was home with her 6-month-old baby. When I arrived to her house I told her about the pain that morning and she asked if I was pregnant. I told her that there was no way but, in my heart, I knew. I drove back home later that evening clenching my teeth as the waves of pain hit me. When I got home I dusted off an old pregnancy test box and held my breath as I waited for the verdict: Pregnant.

I walked out of the bathroom, told my husband the news, and cried. We were both in our final year of graduate school, living in New Jersey – clear across the country from our institutions in California and making regular trips to check-in with our advisors. We were teaching full-time at a nearby university and I was also holding a part time job at a clothing shop. Just a few months earlier I had resolved to finally finish my dissertation and start working on applications for the academic job market. This pregnancy was an unexpected interruption to our plans and, like the schtick of a romantic comedy, we needed more proof. Very quickly we were on our way to the pharmacy to pick up another box of pregnancy tests. On the way to CVS and back I listened and mouthed the words to Hurray for the Riff Raff’s “Go Out on the Road” on repeat. For some reason that song echoed my empty, excited, and sorrowful feelings. We’d just returned from a 3-week cross country road trip, we’d been married for six months, we’d been together for six years, but it felt like we were just getting started. This felt like a fantastic kind of failure. This would end our hopes to move forward and would mean a whole new future. I was thrilled and terrified.

One positive test after another led to a doctor’s visit where a blood test showed that I was indeed pregnant – about five or six weeks, maybe more. The doctor gave me a script for pre-natal vitamins and booked me for a follow-up in a week. There was no ultrasound, no discussion of my ongoing pain and symptoms, just a script and a shrug.

That week my friend, the owner of the clothing shop where I worked on the weekends, was taking the staff on a weekend trip to Puerto Rico. As nervous as I was to be pregnant I was also superstitiously hoping to see my grandmother –mother to 18 children/grandmother to over 100– to get her blessing for my baby who was sure to be one of her last bisnietos (as I was one of her last grandchildren to have a baby and she was well into the double digits on tataranietos). When I went to see my grandmother in Caguas I held her hands tightly and stared deeply into her cataract-laced eyes, saying nothing about my baby as she gave me her bendición: que santa clara te acompañe.

The morning we were due to leave the island, I snuck away at sunrise to take a solo bath in the salt waters of the Atlantic. I thought of my ancestors bathing and rejoicing in those waters, my ancestors carried violently across the sea and worshiping in those waters, and my ancestors who brought their hunger, greed, and despair to those waters. I meditated on my child and summoned up their emotional, ancestral, and ephemeral inheritance to those waters.

Upon return, my second blood test showed that I was miscarrying or had miscarried. My HCG numbers were plummeting and without much explanation, the doctor said the reason was inconclusive – perhaps a blighted ovum or more likely a chromosomal issue with the embryo. These things happen. Whatever the case, I was told that the pregnancy was not viable and was sent on my way. I felt numb. Had I miscarried that August morning back in the apartment or had that been implantation bleeding? Had I miscarried in Puerto Rico or would I miscarry in a few days? Still bleeding a week later, I was left with so many questions that I wouldn’t have answers to for years to come. I know now that I had begun miscarrying that August morning, that the doctors didn’t listen to my symptoms, that they treated me as pregnant when in fact I was losing my baby right in front of them.

The rates of mortality for Black women and infants are twice that of white women in the U.S. and one of the highest of any “developed” nation. We know too well the stories of Black women who were dismissed or ignored, to death. My own mother’s stories of miscarriage and infant death are likewise a documentation of the disregard for Puerto Rican women and their babies in the 1970s. Her first miscarriage led her to bleed out on the train from the Bronx hospital where she was refused help, to Hoboken, NJ where she was rushed into surgery. Her second loss came after being misdiagnosed and medicated for not having enough amniotic fluid. Unbeknownst to her she gave birth prematurely to twin daughters. Only one survived. When I talk about miscarriage and infant loss to my extended kin and community I am met with a flurry and fury of stories: infinite loss, infuriating care, and often the simple reality of the unknown.

When we lost our first baby, I remember that I was consoled only by the thought that perhaps we weren’t ready to be parents just yet. We were wrong.

MATH

I was diagnosed with dyscalculia in 2007 a few months before my college graduation. I felt freed knowing that my visceral reactions to my university math classes were not just a mix of stubbornness and stupidity, but rather a diagnosed disability. I transpose numbers and mix-up equations, I jumble addresses, phone numbers, and codes. My relationship to math has always been as strange and as strong as my transfixing love of words. For many people these worlds are not separate. For me, the use of words and numbers are universes apart.

Over the last three years, the struggle to grow our family has caused me anxieties like I have never known before. The kinds of mental math I make are illogical, absurd, painful, and relentless. There is the equation of deficit – where I calculate where I fall in my family’s fertility matrix:

Abuela Santo: 22 pregnancies, 18 children

Abuela Catalina: 6 pregnancies (?), 6 children, 2 murdered after her own mysterious death

Mami: 5 pregnancies (1 set of twins with 1 surviving), 4 children

Papi: 1 child, 5 stepchildren

Sibling: 1 child

Sibling: 1 child

Sibling: 1 child

Me: 0

In this fucked up equation the number of children decrease with me reasonably getting none.

There is the equation of scarcity, a zero-sum game, where I calculate how many children in my kinship and family networks and frantically attempt to decipher the “chances” that I will have children:

5 couples with twins

2 couples with triplets

7 people on baby #1

12 people on baby #2-3

3 close friends pregnant now

700 acquaintances pregnant now

0 babies for me

In this equation every baby born and every baby announcement make the chances of me having a baby go down and down and down. 0.

Equations like this ...

Grief the size of a lemon seed

Root into a tree,

A sapling taking hold in the root of you in your womb

A blooming halo

Blocking all light and possibility

Offering instead a sobering truth

You are not like the others

You are like many that are not like the others

Your future children, ojala, may bring you joy

but you know what it is to lose

and the fear of loss consumes you

eats your dreams, invades your days

It reaches inside you and scoops and

scrapes away at the hope you’ve been hiding

THE ROAD

We started trying to grow our family in 2016. We had just bought our first home and were so thrilled to be first-generation home owners and in our first jobs after graduate school. It was, a quiet pursuit, our child, and we felt that sharing our desire to become parents would dash our hopes. Keep your head down nena and quietly try for a baby. I started taking pre-natal vitamins and a few months later we spent the summer in Spain and Morocco hoping to come back home pregnant. Months passed and my visits to the ObGyn were inconclusive. My doctor, a white woman, told me to lose 10lbs then 15lbs. My PCOS and weight were the problem she suggested. Every test returned clear. I started taking medicine to help with the insulin resistance that PCOS can cause, medicine that made me extremely sick. Every visit to the doctor ended with an increase of that medication, every visit was a painful reminder that I had to keep waiting for our baby to come. I dropped 15lbs and then 20lbs by cutting calories, exercising, practicing yoga, and going to acupuncture. But returning to the doctor with those results were not enough – she would not recommend me for fertility treatments. I know now that I could have gone to a fertility specialist without a referral but at that point I was blindly following whatever the doctor advised even as she withheld our possibilities.

In 2017 I went to my primary care physician and told her about my fertility struggles. She recommended some blood work and when the results came back she gravely informed me that she thought I had perimenopause. My estrogen levels were low she said, and this was cause for concern. I was then sent for a mammogram. I made an appointment with my ObGyn and waited one week for the appointment. During that week I was alternatively catatonic and then inconsolable. I remember crying quietly through an entire work out at the gym. I remember my husband helping me to my feet in the Target parking lot. Stepping out of the car I had collapsed to the ground in a fit of tears, unable to walk or talk for the pain of the potential diagnosis. At my appointment the nurse on call calmly and lovingly informed me that estrogen is a fluctuating hormone and is not used to determine fertility. You are fine. You are perfectly healthy. You can have babies. I was relieved and enraged at my primary care physician for a potentially devastating diagnosis for which she knew nothing about. I needed a specialist but was still so scared of what that step would mean.

LAW 116

I come from the most sterilized nation in the world. Over the course of twenty-five years law 116 saw to it that over 34% of Puerto Rican women were coerced into sterilization as a form of permanent birth control or rather, population control across the island. The sole method of contraception available at first (besides the male vasectomy), Puerto Rican women were often sterilized without their knowledge or without knowing that the procedure was irreversible. Since winning it as a prize of war in 1898, the colony of Puerto Rico has represented both a problem and wealth of biopolitical resources for the united states. The film La Operación interviews women and they confirm that there was no orientación, no guidance. Puerto Rican women were also used as a laboratory subjects to test the nascent birth control pill which, a strikingly ten times more potent than was eventually made available to women in the United States.

The aim to sterilize this population of non-white peoples did not stay on the island but rather, migrated in the same pattern as the population. Efforts to sterilize Black, Puerto Rican, and working-poor women in the Bronx’s Lincoln Hospital were met with mass protests.

I touch my empty womb. I rage against histories of corporeal dispossession.

Read Part 2 here…

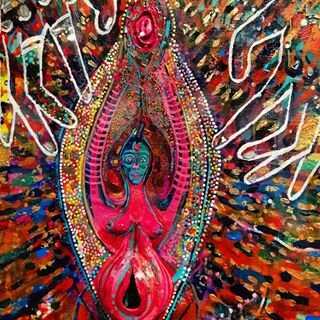

![[found image/artist unknown]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/557d104fe4b020deb8e1339c/1594005564358-AXASOKFBIB5EBPEB1XAX/bin.jpg)